|

|

||||

|

||||

|

Wednesday, February 17, 2016

International Women's Day Luncheon - March 8, 2016

Tuesday, February 16, 2016

Friday, February 12, 2016

Boeing to Face SEC Probe of Dreamliner and 747 Accounting (BusinessWeek)

- Investigation said to review forecasts tied to costs and sales

- Regulator examining company's use of `program accounting'

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating whether Boeing Co. properly accounted for the costs and expected sales of two of its best known jetliners, according to people with knowledge of the matter.

The probe, which involves a whistleblower’s complaint, centers on projections Boeing made about the long-term profitability for the 787 Dreamliner and the 747 jumbo aircraft, said one of the people, who asked not to be named because the investigation isn’t public. Both planes are among Boeing’s most iconic, renowned for the technological advancements they introduced, as well as the development headaches they brought the company.

Underlying the SEC review is a financial reporting method known as program accounting that allows Boeing to spread the enormous upfront costs of manufacturing planes over many years. While the SEC has broadly blessed its use in the aerospace industry, critics have said the system can give too much leeway to smooth earnings and obscure potential losses.

“We typically do not comment on media inquiries of this nature,” Boeing spokesman Chaz Bickers said in an e-mailed statement. SEC spokesman John Nester declined to comment.

Share Drop

Boeing fell 6.8 percent to $108.44 in New York, the lowest closing price in more than two years.

SEC enforcement officials have yet to reach any conclusions and could decide against bringing a case, said the people. The issues involved are complex and there are few black-and-white rules governing how companies apply program accounting, one person said.

Program accounting has been around for decades. It was first championed by the aerospace industry to address the problem that companies’ biggest expenses are amassed upfront, as they design planes and devise manufacturing processes. Costs typically fall as the assembly becomes more efficient, making it cheaper to build the later jets than the earlier ones.

The method, which is fully compliant with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles, lets companies average out the costs and anticipated profits over the duration of the “program” for a specific jet, a period that can last decades and encompass hundreds or even thousands of aircraft.

The expected costs and sales are estimates and they must be updated -- and a loss recorded -- when the program is determined to have reached a point where earnings won’t catch up to losses.

Boeing’s Forecasts

As part of the investigation, SEC enforcement attorneys are examining whether Boeing’s financial statements relied on sales forecasts that might be too optimistic, one person said. Another avenue of inquiry is whether Boeing’s estimates for declining production costs will come to fruition, the person said.

A whistleblower has given SEC officials internal documents and data about Boeing’s accounting, according to the people. The tipster first raised concerns with the regulator more than a year ago, one person said. SEC policy is to not reveal the identities of whistleblowers.

Over the years, a handful of aerospace analysts have questioned whether Boeing will be able to recoup its costs for both the 787 and the latest 747, both of which debuted far behind schedule in 2011. In general, the company has enjoyed a good reputation on Wall Street, earning billions of dollars in annual profits and winning buy recommendations from most researchers who follow the industry.

Boeing’s accounting projects that the company will eventually make money on the Dreamliner despite already spending $28.5 billion on inventory and manufacturing. The forecast hinges on Boeing selling about 1,300 planes and assumes profits on its later deliveries will offset high costs stemming from early production snarls.

The SEC investigation “is potentially material and now a key focus for us,” Seth Seifman, an analyst at JPMorgan Chase & Co., said in a note to clients.

“If the issue here is whether Boeing should have already booked a 787 charge that many believe inevitable, that will be less damaging to the stock,” he said. “If there is any impact on our 787 cash flow forecasts for the coming years, this would be more significant.”

Plateauing Expenses

Boeing told investors during a January conference call that its Dreamliner expenses would plateau this year and then begin to decline as it speeds up production.

“We still have work ahead of us on the 787,” Boeing Chief Executive Officer Dennis Muilenburg said on the call. He added that the company is “focused on solid day-to-day execution and risk reduction, while improving long-term productivity and cash flow.”

Some analysts are skeptical that margins will improve enough to offset money that Boeing has already poured into the 787. Credit Suisse Group AG analyst Robert Spingarn estimated the company may face a $7.5 billion shortfall on the jet, according to a December report.

Boeing’s outlook for the latest and largest version of its jumbo family, known as the 747-8, has also been questioned by some aerospace analysts.

Accounting Losses

Over the years, Boeing has recorded several accounting losses, totaling $2.6 billion, for the 747-8 program. The most recent was last month when the company reported an after-tax loss of $569 million and announced it would halve its production to six jumbos a year.

Boeing’s current accounting estimates for the program’s profitability rely on it selling 35 more 747-8s.

Meeting those numbers could be a challenge. The company has only had 121 orders for the jet since 2005, and most of those sales came before the 2008 financial crisis. In addition, Boeing only netted two 747-8 sales over the previous two years. It ended up buying both planes itself as part of a lease-back deal with a Russian cargo company.

Boeing executives have said they are hopeful of a possible resurgence late this decade for the 747 freighter, whose size and cargo-loading capabilities are unmatched. The company’s other sales prospects for the 747 include replacements for the Air Force One aircraft that ferry U.S. presidents.

Jason Gursky, senior aerospace and defense analyst with Citigroup Inc., isn’t as optimistic.

“We expect the line to fully close early next decade after the Air Force One replacement,” Gursky wrote in a Jan. 22 report. He said the 747 order book is “very weak.”

Thursday, February 11, 2016

Imagine Google's VR gadget without the cardboard. Google does

Google's virtual reality ambitions leave cardboard behind.

The Web giant is planning to release a new VR headset later this year, the Financial Times reported Sunday. A successor to Google's Cardboard VR viewer released in 2014, the new smartphone-based headset would sport improved sensors and lenses housed in a solid plastic casing.

The move would underscore the continuing maturation of VR, which promises to transport goggle-wearing users to digitally created 3D worlds. It's all the rage among big tech companies: Facebook is on the verge of releasing its long-awaited Oculus Rift headset, while Sony, Samsung and HTC are also heavily invested in the technology.

Microsoft's HoloLens, meanwhile, is aimed at augmented reality, which adds 3D computer-generated scenes to people's view of the real world. Apple has also reportedly assembled a secret research group focused on virtual and augmented reality.

VR's potential extends well beyond the early emphasis on its use in video games, virtual field trips and reboots of classic toys. Backers say it could radically change the way we use computers, with ripple effects into how we communicate with one another.

Apple CEO Tim Cook last month summed up the fascination. "I don't think it's a niche," he said. "It's really cool. It has some interesting applications."

Whether consumers will bite, though, remains a mystery. Samsung has yet to reveal sales figures for its Gear VR headset, which was released last year for $99 (£80 in the UK or AU$159 in Australia), not including the price of a smartphone to power it. Other major devices, ranging from the $599 (£499 or AU$649) Oculus Rift to HTC's Vive to Sony's PlayStation VR are all expected to be released this year.

With Cardboard, Google took a bargain-basement tack. For $30 or less, consumers get a corrugated-paper housing for the smartphone they already own, with cutouts for nose and eyes. An app on the phone delivers the VR experience as cardboard blinders shut out the viewer's surroundings. Little more than a party favor, Google Cardboard could serve as a gateway drug to get people hooked on VR.

Google declined to comment for this story, but CEO Sundar Pichai last week signaled the Mountain View, California-based company's continued interest in virtual reality. He noted that more than 5 million Cardboard viewers have been shipped.

"It's still incredible early innings for virtual reality as a platform," Pichai said during an earnings conference call. "Cardboard is just a first step, but we are excited by the progress we have seen."

Tuesday, February 9, 2016

The Rich Are Already Using Robo-Advisers, and That Scares Banks (BusinessWeek)

- Are Robo-Advisers Better Than Humans?

- About 15% of Schwab's robo-clients have at least $1 million

- Morgan Stanley, Wells Fargo, BofA planning automated services

Banks are watching wealthy clients flirt with robo-advisers, and that’s one reason the lenders are racing to release their own versions of the automated investing technology this year, according to a consultant.

Millennials and small investors aren’t the only ones using robo-advisers, a group that includes pioneers Wealthfront Inc. and Betterment LLC and services provided by mutual-fund giants, said Kendra Thompson, an Accenture Plc managing director. At Charles Schwab Corp., about 15 percent of those in automated portfolios have at least $1 million at the company.

“It’s real money moving,” Thompson said in an interview. “You’re seeing experimentation from people with much larger portfolios, where they’re taking a portion of their money and putting them in these offerings to try them out.”

Traditional brokerages including Morgan Stanley, Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co. are under pressure to justify the fees they charge as the low-cost services gain acceptance. The banks, which collectively employ about 46,000 human advisers, will respond by developing tools based on artificial intelligence for their employees, as well as self-service channels for customers, Thompson said.

“Now that they’re starting to see the money move, it’s not taking very long for them to connect the dots and say, ‘Whatever I offer for a fee better be better than what they’re offering for almost nothing,”’ Thompson said. Technology will “make advisers look smarter, better, stronger and more on top of the ball.”

Keeping Humans

Robo-advisers, which use computer programs to provide investment advice online, typically charge less than half the fees of traditional brokerages, which cost at least 1 percent of assets under management. The newer services will surge, managing as much as $2.2 trillion by 2020, according to consulting firm A.T. Kearney.

More than half of Betterment’s $3.3 billion of assets under management comes from people with more than $100,000 at the firm, according to spokeswoman Arielle Sobel. Wealthfront has more than a third of its almost $3 billion in assets in accounts requiring at least $100,000, said spokeswoman Kate Wauck. Schwab, one of the first established investment firms to produce an automated product, attracted $5.3 billion to its offering in its first nine months, according to spokesman Michael Cianfrocca.

Bank leaders including Morgan Stanley Chief Executive Officer James Gorman and Wells Fargo Chief Financial Officer John Shrewsberry have said their firms must develop robo-advisers to complement their sales force.

Customers want both the slick technology and the ability to speak to a person, especially in volatile markets like now, Jay Welker, president of Wells Fargo’s private bank, said in an interview.

“Robo is a positive disruptor,” Welker said. “We think of robo in terms of serving multi-generational families.”

Monday, February 8, 2016

Friday, February 5, 2016

Why You're Still Paying Fuel Surcharges After the Oil Crash (BusinessWeek)

Zombie fuel fees maintain a grip on airlines and other companies.

The collapsing price of oil that has upended the global economy has also caused understandable rejoicing at transportation companies, where big savings from cheap fuel will inevitably show up in the bottom line. Yet many of the surcharges that truckers, railroads, and—especially—airlines tacked on during the years of expensive oil have proven resilient. Travelers and other customers are still paying these zombie fuel fees even now, with crude at $32 per barrel.

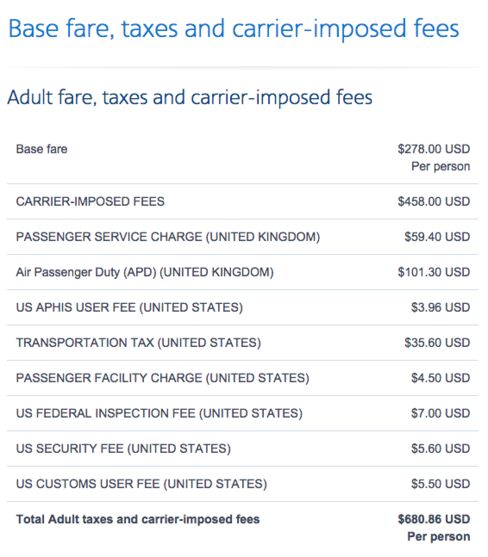

Here are the fare, taxes, and surcharges from a randomly selected American Airlines flight from Los Angeles to London in February. You won’t see anything labeled “fuel surcharge,” but that doesn’t mean you’re not paying an extra fee held over from the days when crude sold for more than $100 per barrel.

Unlike their peers in rail and trucking, U.S. airlines retired the term “fuel surcharge” in response to a 2012 ruling from the U.S. Department of Transportation that required carriers to demonstrate some relationship between a fuel-related fee and the price of fuel. Few airlines wanted to shed the surcharge, however, so international air travelers now pay hundreds of dollars in “carrier-imposed fees” or “carrier fees” instead. Airline ticketing software groups these fees under the designation “YR,” a catch-all category that can cover a fuel surcharge, insurance, and whatever else an airline sees fit to tack on to the base fare. Airlines don’t have these surcharges on domestic itineraries.

“The airlines have been very careful to shroud everything in as much mystery as possible,” says Charles Leocha, founder of Travelers United, a consumer-advocacy group.

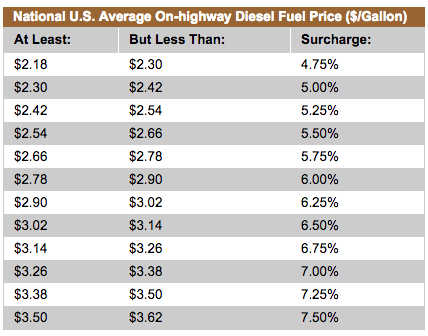

Only cruise lines have abolished fuel surcharges as energy costs have dropped off precipitously. Airlines, major trucking companies, shippers such as FedEx and UPS, and railroads all continue to assess fuel surcharges in the normal course of business. The cargo haulers tend to publish tables of their surcharges, which are pegged to market prices. Here’s one from UPS for ground shipments:

Current fuel surcharge schedule for UPS ground shipments.

UPS

The monthly rates at both FedEx and UPS have steadily dropped, as in the table above, falling in tandem with fuel costs. UPS has a 4.25 percent surcharge for air shipments, down from 16 percent in July 2011, according to BirdDog Solutions, a Hickory, N.C.-based shipping consultant. Over the past year, UPS and FedEx surcharges for air cargo have dropped 2.8 percent and 2.3 percent, respectively, the firm said.

Airlines don’t publish similar surcharge schedules, and the vagueness serves an important purpose: Many big-volume corporate travel buyers get their airline discount applied to base fares, while surcharges are paid in full. The passenger airline surcharges have averaged about $450 round-trip on trans-Atlantic itineraries for about three years and fluctuate very little, said Rick Seaney, chief executive of FareCompare.com, which monitors the data monthly. Surcharges to Asia and South America average between $420 and $440. On some international tickets, Seaney said, the surcharges cost more than the base fare.

“The whole thing is crazy, really,” says Bob Harrell, who runs a consulting firm that tracks airfares. “It started out as something that made sense, but it’s morphed into something that doesn’t make sense. After [airlines] got the fares up, they didn’t want to bring them down.”

That’s because the surcharges are an important part of airlines’ profitability. These fees “reflect a variety of factors and market forces that vary from market to market,” said Vaughn Jennings, a spokesman for Airlines for America, which represents most of the large U.S. carriers. “Airline pricing decisions and how prices are constructed are made individually by carriers in the highly competitive market for air transportation.” Moreover, Jennings said, these charges are included in the total price consumers see before they purchase.

The American way of handling surcharges isn't mirrored in other markets. Airlines in Japan—which regulates surcharges—and South Korea have begun abandoning these fees in recent weeks. Australia’s Qantas began rolling them into base fares a year ago. Hong Kong's Civil Aviation Department has banned fuel surcharges for flights originating there effective Feb. 1 because fuel prices have “greatly reduced and stabilized to a reasonable level,” the agency said.

The drop in fuel expenses also presents a financial issue for airlines keen to retain fuel surcharges as a way to bolster income. On Delta Air Lines’ recent quarterly earnings call, an analyst questioned how close the airline is to the lower edge of fuel surcharges in Japan. “In the past we’ve been able to roll those surcharges into the base fares as they changed, but I'm not predicting what the future is, nor do we want to comment on how we think that will roll out in the future,” replied Glen Hauenstein, Delta’s chief revenue officer. On its website, meanwhile, Delta notes the fees can total as much as $650 each way.

The high price of surcharges has embarrassed airlines in the past. In 2013, for instance, American apologized to some customers after applying fuel surcharges as high as $700 to some tickets issued with award miles. But that hasn't prompted the carriers to rethink the reliance on these fees. While lower fuel costs have provided a huge windfall in the transportation sector, many companies have been caught on the wrong side of expensive fuel hedging contracts. For example, Delta, Southwest, and United booked combined losses north of $1 billion last year for having locked in fuel at above-market prices. (The largest airline, American, does not hedge fuel.) Along with cheaper spot fuel prices, surcharges help lessen the sting of hedge losses and provide a backstop should prices spike.

Most truck carriers likewise have a wide range of surcharges and negotiate each of these with their customers individually, said Sean McNally, a spokesman for the American Trucking Associations. Most trucking companies and railroads consider fuel surcharges a form of insurance, according to Lee Klaskow, a Bloomberg Intelligence rail and trucking analyst. It's just another way to hedge against the cost of fuel. “For trucking,” Klaskow said, “if you say the rate is this and a component of that rate is going to float to the price of fuel, then you’re pretty much covering your tush.”

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)