Zombie fuel fees maintain a grip on airlines and other companies.

The collapsing price of oil that has upended the global economy has also caused understandable rejoicing at transportation companies, where big savings from cheap fuel will inevitably show up in the bottom line. Yet many of the surcharges that truckers, railroads, and—especially—airlines tacked on during the years of expensive oil have proven resilient. Travelers and other customers are still paying these zombie fuel fees even now, with crude at $32 per barrel.

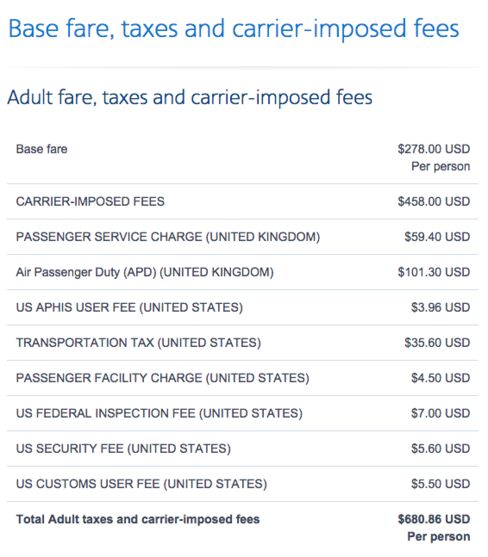

Here are the fare, taxes, and surcharges from a randomly selected American Airlines flight from Los Angeles to London in February. You won’t see anything labeled “fuel surcharge,” but that doesn’t mean you’re not paying an extra fee held over from the days when crude sold for more than $100 per barrel.

Unlike their peers in rail and trucking, U.S. airlines retired the term “fuel surcharge” in response to a 2012 ruling from the U.S. Department of Transportation that required carriers to demonstrate some relationship between a fuel-related fee and the price of fuel. Few airlines wanted to shed the surcharge, however, so international air travelers now pay hundreds of dollars in “carrier-imposed fees” or “carrier fees” instead. Airline ticketing software groups these fees under the designation “YR,” a catch-all category that can cover a fuel surcharge, insurance, and whatever else an airline sees fit to tack on to the base fare. Airlines don’t have these surcharges on domestic itineraries.

“The airlines have been very careful to shroud everything in as much mystery as possible,” says Charles Leocha, founder of Travelers United, a consumer-advocacy group.

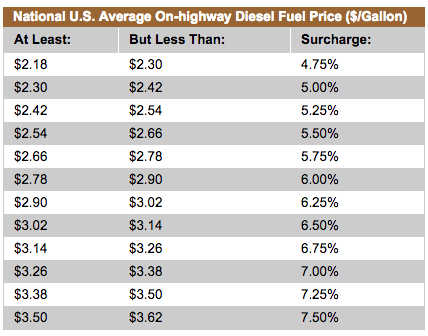

Only cruise lines have abolished fuel surcharges as energy costs have dropped off precipitously. Airlines, major trucking companies, shippers such as FedEx and UPS, and railroads all continue to assess fuel surcharges in the normal course of business. The cargo haulers tend to publish tables of their surcharges, which are pegged to market prices. Here’s one from UPS for ground shipments:

Current fuel surcharge schedule for UPS ground shipments.

UPS

The monthly rates at both FedEx and UPS have steadily dropped, as in the table above, falling in tandem with fuel costs. UPS has a 4.25 percent surcharge for air shipments, down from 16 percent in July 2011, according to BirdDog Solutions, a Hickory, N.C.-based shipping consultant. Over the past year, UPS and FedEx surcharges for air cargo have dropped 2.8 percent and 2.3 percent, respectively, the firm said.

Airlines don’t publish similar surcharge schedules, and the vagueness serves an important purpose: Many big-volume corporate travel buyers get their airline discount applied to base fares, while surcharges are paid in full. The passenger airline surcharges have averaged about $450 round-trip on trans-Atlantic itineraries for about three years and fluctuate very little, said Rick Seaney, chief executive of FareCompare.com, which monitors the data monthly. Surcharges to Asia and South America average between $420 and $440. On some international tickets, Seaney said, the surcharges cost more than the base fare.

“The whole thing is crazy, really,” says Bob Harrell, who runs a consulting firm that tracks airfares. “It started out as something that made sense, but it’s morphed into something that doesn’t make sense. After [airlines] got the fares up, they didn’t want to bring them down.”

That’s because the surcharges are an important part of airlines’ profitability. These fees “reflect a variety of factors and market forces that vary from market to market,” said Vaughn Jennings, a spokesman for Airlines for America, which represents most of the large U.S. carriers. “Airline pricing decisions and how prices are constructed are made individually by carriers in the highly competitive market for air transportation.” Moreover, Jennings said, these charges are included in the total price consumers see before they purchase.

The American way of handling surcharges isn't mirrored in other markets. Airlines in Japan—which regulates surcharges—and South Korea have begun abandoning these fees in recent weeks. Australia’s Qantas began rolling them into base fares a year ago. Hong Kong's Civil Aviation Department has banned fuel surcharges for flights originating there effective Feb. 1 because fuel prices have “greatly reduced and stabilized to a reasonable level,” the agency said.

The drop in fuel expenses also presents a financial issue for airlines keen to retain fuel surcharges as a way to bolster income. On Delta Air Lines’ recent quarterly earnings call, an analyst questioned how close the airline is to the lower edge of fuel surcharges in Japan. “In the past we’ve been able to roll those surcharges into the base fares as they changed, but I'm not predicting what the future is, nor do we want to comment on how we think that will roll out in the future,” replied Glen Hauenstein, Delta’s chief revenue officer. On its website, meanwhile, Delta notes the fees can total as much as $650 each way.

The high price of surcharges has embarrassed airlines in the past. In 2013, for instance, American apologized to some customers after applying fuel surcharges as high as $700 to some tickets issued with award miles. But that hasn't prompted the carriers to rethink the reliance on these fees. While lower fuel costs have provided a huge windfall in the transportation sector, many companies have been caught on the wrong side of expensive fuel hedging contracts. For example, Delta, Southwest, and United booked combined losses north of $1 billion last year for having locked in fuel at above-market prices. (The largest airline, American, does not hedge fuel.) Along with cheaper spot fuel prices, surcharges help lessen the sting of hedge losses and provide a backstop should prices spike.

Most truck carriers likewise have a wide range of surcharges and negotiate each of these with their customers individually, said Sean McNally, a spokesman for the American Trucking Associations. Most trucking companies and railroads consider fuel surcharges a form of insurance, according to Lee Klaskow, a Bloomberg Intelligence rail and trucking analyst. It's just another way to hedge against the cost of fuel. “For trucking,” Klaskow said, “if you say the rate is this and a component of that rate is going to float to the price of fuel, then you’re pretty much covering your tush.”

No comments:

Post a Comment